- Home

- O'Connor, Sheila

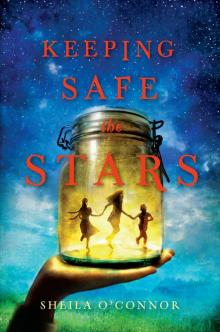

Keeping Safe the Stars (9781101591215)

Keeping Safe the Stars (9781101591215) Read online

ALSO BY SHEILA O’CONNOR

Sparrow Road

Where No Gods Came

Tokens of Grace: A Novel in Stories

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS • A DIVISION OF PENGUIN YOUNG READERS GROUP.

Published by The Penguin Group.

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto,

Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.).

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England.

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd).

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd).

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhi—110 017, India.

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632,

New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd).

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank,

Johannesburg 2196, South Africa.

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England.

Copyright © 2012 by Sheila O’Connor.

All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any

form without permission in writing from the publisher, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, a division

of Penguin Young Readers Group, 345 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014.

G. P. Putnam’s Sons, Reg. U.S. Pat. & Tm. Off. The scanning, uploading and distribution

of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher

is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do

not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of

the author’s rights is appreciated. The publisher does not have any control over and does

not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Published simultaneously in Canada. Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

O’Connor, Sheila.

Keeping safe the Stars / Sheila O’Connor.

p. cm.

Summary: In rural Minnesota in 1974, thirteen-year-old Pride Star,

raised to be independent, must accept help from friends and neighbors to care

for eleven-year-old Nightingale and six-year-old Baby when her grandfather

is hospitalized with a brain infection.

[1. Self-reliance—Fiction. 2. Sick—Fiction. 3. Family life—Minnesota—Fiction.

4. Neighborliness—Fiction. 5. Orphans—Fiction. 6. Old age—Fiction.

7. Minnesota—History—20th century—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.O22264Kee 2012

[Fic]—dc23

2011038846

ISBN 978-1-101-59121-5

For

Bobby and Georgia O’Connor,

who taught us all what it means to be a family

and

Mikaela, Dylan, and Tim Frederick,

because everything begins and ends with you.

Contents

ALSO BY SHEILA O’CONNOR

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

1. WAIT

2. SELF-RELIANCE

3. MAKING DO

4. PRIDE’S FIRST LIE

5. DOER; DREAMER; DARER

6. OLD FINN

7. IMPEACH

8. READY NOW OR NOT

9. WISH YOU WERE HERE

10. MAKE-BELIEVE

11. HOOT

12. GONE

13. SELF-RELIANCE

14. KEEPSAKES

15. DEAR MICK

16. PONY RIDES AND POPCORN

17. NOT TELLING

18. AN EVENING TREAT

19. TWO SOLITARY SOULS

20. SUGAR SMACKS AND COFFEE

21. FRIENDLY QUESTIONS

22. OFF THE BEATEN TRACK

23. HELTER-SKELTER

24. REAL AND TRUE

25. HARD TIMES

26. SOMEONE HERE TO HELP

27. HOW BROKEN MY HEART

28. THE MISSING LIST

29. SHELTER

30. NO ONE ELSE’S STORY

31. NOT ANY NUMBER HERE

32. CABIN FEVER

33. COULD BE THIS AFTERNOON

34. ANOTHER KIND OF STAR

35. CHASED

36. A DOLLAR OUGHT TO DO IT

37. CLOSED

38. NO ONE BUT OLD FINN

39. HISTORIC

40. SOME DUMB THING

41. ALL I NEED TO KNOW

42. SOMETIMES YOU’RE JUST WRONG

43. SLOW, BUT SURE

44. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD

45. CLOSER TO A GROWN-UP

46. FIVE THIN DIMES

47. HOPING ON A STRANGER

48. I KNOW WHO YOU ARE

49. OLD FINN AND JUSTINE

50. OUR SHADOW

51. IN THE DARK

52. ALMOST FAMOUS

53. LIKE EVERYBODY ELSE

54. LOVED

55. THE ONE TO WATCH YOU NOW

56. A HOPE THAT SOMEONE HEARD

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

1

WAIT

It was Old Finn who sent us down the wood path to Miss Addie’s. First he kissed us each good-bye and told us not to worry, then he said to stay put in Miss Addie’s tiny trailer until he came home from St. John’s.

Which is exactly what we did—me and Nightingale and Baby—we sat there at Miss Addie’s cutting photographs from movie magazines, building paper towns, and stringing necklaces from noodles. We waited and we worried, even though Old Finn had told us that we shouldn’t.

When darkness finally came, I opened Miss Addie’s tattered phone book and hunted down the number for St. John’s Hospital in town. “It’s been too long,” I said. “Old Finn only went in for a fever.”

“He must be sick,” Miss Addie said, concerned. “Your grandpa can’t abide a doctor, so for him to drive into St. John’s . . .”

Nightingale set down her noodle necklace; I saw my own fear cross her silent face. I knew what she was thinking—she was thinking same as me—What if something bad had happened to Old Finn? Old Finn was our only known family, the last one left to love us. If we lost him, we’d end up all alone. At eighty-three, Miss Addie was too old to raise three kids.

“Maybe we should wait,” Nightingale said.

“No,” I said. “By now, Old Finn ought to be home.” Somehow facing down our troubles was always up to me. Baby was just six and Nightingale too timid. Old Finn always said it was the burden of the oldest to see the worst before everybody else, to be on the watch for trouble so the younger Stars stayed safe.

I put my finger in the dial and started with the three. 3-6-7. Everyone was watching; I couldn’t hear a single breath. “But, Pride . . . ,” Nightingale started like she wanted me to stop. Her serious black eyes were full of worry.

“Perhaps I should be the one to speak,

” Miss Addie offered weakly. She stood up from her chair and shuffled toward the phone.

“Okay,” I said. I knew St. John’s would tell a grown-up more about a fever, even if Miss Addie wasn’t half as self-reliant as the Stars. Most days it was us who tended to Miss Addie.

We all sat there still as stone while we watched Miss Addie listen. “Oh dear,” she finally said, and I heard in her hushed voice the news was bad. Baby snuggled close against my chest. “Well, yes, I’m the next of kin,” Miss Addie answered, flustered. “Let me leave my number.” Next of kin meant “family,” but Miss Addie wasn’t that. I couldn’t believe Miss Addie had just lied. “All right,” she said. “Thank you for your help.”

She hung the heavy phone back on its hook, took a few long breaths like she was weighing how much trouble she ought to tell three kids. “I’m afraid,” she said, a nervous warble rising in her voice. She fiddled with her wig of snowy ringlets. “Old Finn has some kind of infection. Some trouble with his brain.”

“His brain?” Nightingale gasped. Old Finn’s brain was full of history and Latin, algebra and physics, geography and ancient Greece. He had a head packed full of knowledge, some he tried to teach to us. Square roots, symphonies, and sonnets. “Old Finn can’t lose his brain.”

“Not lose.” Miss Addie tried to say it cheerful, but still she worked her wrinkled hands into a knot. “Hopefully his trouble will just pass.”

“But when’s he coming back to Eden?” Baby asked. “Before we go to sleep?”

“Probably not,” I said, because I knew the answer without Miss Addie even saying. I rubbed my hand over Baby’s soft brown bristles. Baby kept his head shaved like Old Finn, wore matching Wrangler jeans, cowboy boots they both bought at Newport Saddle. He’d been a miniature Old Finn ever since we moved to Eden.

“I imagine I’ll have to keep you children here,” Miss Addie said like she wasn’t really certain.

“Here?” Baby’s eyes grew huge. Miss Addie only had one narrow bed. There wasn’t any place for us to sleep. The tiny trailer floor was covered with our crafts.

“But we’re Old Finn’s next of kin,” Nightingale said, matter-of-fact. She was tucked up in the rocker, her knees up to her neck, her ruffled nightgown draped over her thin legs, her long black braids brushing her bare feet. “Why didn’t you tell the truth?”

“Oh dear.” Miss Addie shrugged, ashamed. “I didn’t know what else to say.” She shook her head like she wished she hadn’t lied. “But when it comes down to you children, your grandpa doesn’t want me passing information.”

I thought about the visits from the county, how Old Finn worried every time that school woman came to check our lessons. Or how in Goodwell he’d walk away from questions he didn’t like. It’s not anybody’s business how we live at Eden, Old Finn always said.

“Miss Addie’s right,” I said to Nightingale. “Old Finn wouldn’t want a soul to know he’s sick, or that we’re left at Eden on our own. Even for one night.”

“Maybe more,” Miss Addie said as gently as she could. “We can’t be certain what the future holds.”

2

SELF-RELIANCE

Old Finn always joked he inherited Miss Addie—a retired, eccentric actress—as if she were some kind of keepsake his bachelor uncle, William Martin, left behind when he died and willed Eden to Old Finn. I only knew she’d been living on this land for years and years, long before Old Finn came from California; and when he made his home on William Martin’s forty acres, Miss Addie just stayed put. Miss Addie and her craft projects and costumes, magazines and records, her little black-and-white TV, mounds of clutter that filled up most of the trailer.

“I’m afraid I wasn’t set for company,” Miss Addie fussed when she woke up the next morning. She looked ancient in her housedress, shrunk down to bone with sags of pale, paper skin. I missed her layers of makeup, her strings of beads and bangles, the lively flowered muumuus she wore during the day. “I’ve only got a smidgen left of milk. One small dish of Wheaties.”

“That’s okay,” I said. After a night on Miss Addie’s scratchy carpet, one flimsy sheet spread over us all, I was ready to head home. “We have plenty at the cabin.” I sat up, gave Nightingale a nudge. I didn’t want Miss Addie to feel bad about the food; she’d already divided her last can of mushroom soup for supper. Filled us up on stale saltines. “Come on, Baby.” I shook his little shoulder. “It’s morning now; we need to head on home.”

“Home?” Baby rubbed his eyes.

Nightingale pulled the sheet up to her chin. “Home without Old Finn?”

“You sure you children can fix breakfast for yourselves?” Miss Addie asked.

“I’m thirteen,” I said. “Been thirteen for three weeks. And Nightingale’s on her way to twelve. Plus breakfast is my job.” We all had jobs at Eden; Old Finn had been preaching self-reliance since the first day that we came. Nearly two years straight of self-reliance lessons. Independence. Even though I’d been standing steady on my own two feet since the day I learned to walk. Still it was Old Finn’s self-reliance that taught me how to fix a toilet, change a fuse, brew potato soup for supper, weed the garden, and chop wood. It’s why we had our school at his table instead of going into Goodwell like everybody else. After all that training, I didn’t need Miss Addie’s Wheaties to get by. “And until Old Finn gets done with his fever, we’re going to have to practice independence, rise to the occasion.” Rise to the occasion was Old Finn’s famous phrase—it meant tackling a problem whether you wanted to or not.

“I’ll rise!” Baby jumped up to his feet. “I’ll fry up the sausage. Spread jelly on the toast. Shoot a squirrel for supper.”

I laughed at that last part; Baby always had a dream to hunt.

“Miss Addie, why don’t you come with us to the cabin?” Nightingale urged. Miss Addie hardly ever left her trailer. Like Old Finn, she was happiest at home. “You can be our family for today.”

“Oh dear.” Miss Addie sighed. “It’s such a long walk on that wood path, and Lady Jane will frighten if I leave.” Right now, Miss Addie’s golden tabby was curled up in her lap, but mostly Lady Jane stalked mice in the meadow or dozed lazy on the hood of Old Finn’s truck.

“Lady Jane won’t mind it for one day,” Nightingale argued. I could tell she didn’t want to go back to our cabin without a grown-up along, even one as frail as Miss Addie. Nightingale wasn’t ready to face Eden all alone.

• • •

It was sad and strange to cross the dewy meadow, to know the cabin would be empty, that Old Finn would be gone. Atticus and Scout grazed peaceful in the pasture, but Old Finn’s shadow, Woody Guthrie, moped sad-eyed in the yard. “Oh no,” I moaned. In the worry of the night, Woody Guthrie had gone without his supper. Summers, Old Finn let the horses eat free off the land, but Woody Guthrie needed to be fed.

I called Woody Guthrie’s name, gave a couple claps. Nightingale and Baby called him, too, but he just stayed there, staring; his spotted hound-dog head hung between his paws; his floppy ears draped on the ground like he didn’t want to move an inch with Old Finn gone.

I ran ahead, left Nightingale and Baby to meander with Miss Addie; Miss Addie never moved too fast. Inside the silent cabin, Old Finn’s coffee mug sat empty on the table; his dusty work boots stood beside the door. I grabbed Woody Guthrie’s bowl and filled it with the last crumbs of broken kibble. Like Miss Addie’s milk and Wheaties, Woody Guthrie’s food was nearly gone.

I opened up the pantry. Old Finn’s scribbled grocery list was taped up to the door. Friday was his shopping day in Goodwell, but when Friday came he’d barely left his bed. I added Miss Addie’s milk and Wheaties, Woody Guthrie’s Alpo.

I grabbed the eggs from the refrigerator, put a pat of butter in the pan, set the plates out on the table, poured Baby his milk. I was doing first things first, the way Old Finn always taught me. First I’

d feed my family, then I’d ride to town for groceries. Groceries and a visit to St. John’s.

3

MAKING DO

I’m riding in on Atticus,” I said. I ran the water on our dishes, scrubbed the film of fried egg from our plates. “I’ll leave him at the Junk and Stuff with Thor, just the way I’ve done it with Old Finn.” Now and then, Old Finn and I would set off for a ride, a time for just the two of us to talk. And Thor’s place was the closest you could get a horse to town.

“Alone?” Miss Addie rubbed her neck. I was glad she’d painted makeup on her face, clipped on her emerald earrings, put on a bright green muumuu; she didn’t look quite so fragile anymore. “But it’s another mile at least from the Junk and Stuff to town. You’d have to walk that highway.”

“I can do all that, Miss Addie,” I said. “I’ve got to shop for groceries. Old Finn couldn’t go on Friday, and you need your milk and Wheaties; Woody Guthrie’s kibble is all gone.”

“I’ll go, too,” Nightingale offered.

“You will?” I asked. Like Old Finn and Miss Addie, Nightingale hardly ever wanted to leave Eden. “You’ve got to put on town clothes.”

“I know.” She frowned. Nightingale dressed in nightgowns the way other kids wore jeans. Flannel in the winter; cotton in the summer. Ruffled sleeves and fancy collars all year round. And she was always in bare feet. She’d been that way since we were little; it’s how Mama landed on that nickname: Nightingale. It was the word Nightingale gave the sleep gowns Mama sewed. “I want another nightingale,” she’d beg. And Nightingale stuck.

When we moved in with Old Finn, he didn’t make a stink about the nightgowns, so long as Nightingale put on clothes for town. It’s why she went to Goodwell only for the library and ice cream, a visit to the doctor now and then.

“Me, too!” Baby said. “I’m going into Goodwell.”

“I can’t take you, Baby. Not today.” I didn’t want Baby with me at St. John’s, not until I saw Old Finn myself. “You stay here with Miss Addie.”

“Yes.” Miss Addie patted his small hand. “I need a friend here, Baby.”

Keeping Safe the Stars (9781101591215)

Keeping Safe the Stars (9781101591215)