- Home

- O'Connor, Sheila

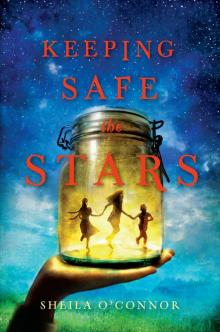

Keeping Safe the Stars (9781101591215) Page 2

Keeping Safe the Stars (9781101591215) Read online

Page 2

While Nightingale climbed up to our loft to dig through clothes, I sat at the table to work with Old Finn’s list. Some things he’d written, like liverwurst and rump roast, razor blades and Borax, could wait till he was well. Miss Addie knew exactly what she needed: Velveeta, macaroni, Wheaties, Wonder Bread, and milk. Seven different kinds of Campbell’s soup. Oscar Mayer bologna. Gingersnaps and fresh saltines.

“I’m not sure what to buy,” I told Miss Addie. “Old Finn makes the list; I just help him cook.”

“It’s easiest to think about the week,” Miss Addie said. “Buy foods you can repeat, like macaroni. That’s the way I do and I get by.”

“Food we can repeat?” I said to Baby.

“Chocolate cake!” he clapped.

“That does sound delicious,” Miss Addie added.

I opened up Old Finn’s Goodwell Baptist cookbook and found the recipe I used for chocolate cake. We had everything I’d need except for eggs; I’d fried the last of them for breakfast. “We’re all out of eggs,” I said. “But I can buy those at the Junk and Stuff from Thor.”

“First we ought to figure out the money, Pride,” Nightingale called down from the loft. “We’ll need it to buy groceries.”

I hadn’t thought about the money; I only knew we needed food to eat. It was Nightingale who had the gift for numbers. Letters, too. Of all of us, she took to Old Finn’s schooling best. While I was tending to the horses or working in the woodshop with Old Finn, Nightingale balanced Old Finn’s ledger, helped figure out the bills. She knew how money worked and where it went.

“Old Finn keeps ten dollars in the coffee can,” she said. “But ten dollars won’t go far.”

I looked over at Miss Addie. Grown-ups had money. She could pay for food, just like she paid for movie magazines.

“I’m afraid I didn’t earn much as an actress,” Miss Addie said. “I write my list; your grandpa buys my groceries.” I could tell she was embarrassed to have Old Finn buy her food. “But I never ask for much.”

“You don’t have any money?” Baby said. “Not a penny in your piggy bank?” Baby’s piggy bank of pennies was a washed-clean tobacco tin.

“Just my two JFK half-dollars I’ve saved as souvenirs. But I’d hate to spend my souvenirs for soup.” Miss Addie kept her JFKs hidden in her closet in a tiny velvet box with Lovecraft Jewelry written on the top. Sometimes she’d take them out to give a look or remember JFK. I wasn’t spending Miss Addie’s souvenirs; I’d buy her groceries same as Old Finn did.

“We have ten at least,” I said. “That ought to be enough.”

I climbed up on the counter, opened up the highest cupboard where Old Finn’s secret coffee can was kept. Money for emergencies. One ten-dollar bill was folded up inside. “I’ll just buy the little that we need. We’ve got potatoes in the pantry. Applesauce. Canned peaches we can eat.”

“That’s the spirit,” Miss Addie said. “And I can go without the gingersnaps and crackers. Velveeta, too. I can eat my macaroni with a little dab of butter.”

“Butter?” Baby said. “I used the last for toast.”

Butter, I wrote down on my list. Milk. Eggs. Bread. We could live awhile on sugar sandwiches and eggs.

4

PRIDE’S FIRST LIE

Woody Guthrie wanted to go with us, but halfway down the driveway I forced him to turn home. I had plans that didn’t include a dog.

I rode up tall on Atticus the way Old Finn always did, while Nightingale trailed behind on Scout. At thirteen, I was a foot too tall to ride right on a pony, and Old Finn promised by the time I turned fourteen, I’d have a quarter horse like Atticus to ride. Nightingale was on the small side of eleven; she could ride another couple years on Scout. And Nightingale never rode Scout much outside of Eden; mostly it was me who liked the long rides with Old Finn.

When we reached the Junk & Stuff, I slid down off the saddle and opened up Thor’s rusted corral gate. Maybe once there’d been horses on his land, but now it wasn’t much more than a patch of weeds beside a weathered barn. “You girls come without Old Finn?” Thor asked. He was one of the only almost-friends Old Finn had in Goodwell. Thor and Nosy Nellie, the woman who sold Old Finn’s wooden birds at the Northwood Nook in town.

“Yeah,” I said. “We’re riding in for groceries.”

“Groceries?” Thor took off his seed cap and ran his hand over his bald head. In his dirty blue-jean bibs and ragged flannel shirt, Thor looked like a skinny scarecrow stuck out in some field. His face was long and blank, his nose too big, his crooked smile full of yellowed teeth. “Don’t your grandpa drive into Goodwell for the groceries?”

“The truck’s run into trouble,” I lied. I’d spent the long ride getting ready for that story, thinking to myself just how I’d say it, letting Nightingale know it was ahead. A lie that wasn’t any different from Miss Addie’s next of kin. But the second that I said it, I had the sinking feeling Thor could see it in my eyes, the place Old Finn always said a lie would show.

“That so?” Thor gave a glance at Nightingale. “And what’s this one’s name again?” I was glad she’d traded in her gown for my old cutoff jeans. My cutoffs and a faded cotton T-shirt Mama used to wear. Clothes so big they bagged around her tiny body, but Nightingale never wanted to buy clothes of her own.

“Elise,” I said. We always used our given names in town. Baby’s name was Baxter; my real name was Kathleen, but at Eden, safe with family, we all preferred the nicknames Mama gave us long ago.

“Well, her braids are almost dragging in the dirt,” Thor joked, but Nightingale didn’t give back a laugh. They weren’t dragging in the dirt, but they hung long, just beyond her waist; maybe in a few more years they’d drag down to the dirt. “Wish I had a head of hair like that,” Thor said with a wink. The only hair Thor had was a little band of white between his ears.

“She’s been growing out her hair since she was six,” I answered to be friendly. Nightingale hardly had a word for anyone but family, family and Miss Addie and that beehived hairdo lady at the library who helped her pick out books. “And she’s eleven now, so that’s five long years of hair.”

I took the tack off the horses, hung it on the fence, pulled the hose over to the trough, and turned it on. I’d done this same routine enough times with Old Finn, and every time, Thor just stood by like a scarecrow and watched. People on his land didn’t bother Thor.

“So that’s the trick,” Thor said with a wink. “Think five years would grow this hair of mine?”

“Probably not,” I said, embarrassed. Thor hardly had hair enough to grow.

“Well, all that hair can’t take the place of shoes.” Thor nodded down toward Nightingale’s feet.

“She’s got shoes there in her sack,” I said. Nightingale wasn’t going barefoot to St. John’s.

Thor sank his hands into the pockets of his rumpled overalls; every time I saw Thor he was dressed in blue-jean bibs. Same way Nightingale wore gowns, and Old Finn wore his Wranglers and plaid shirts. I liked pastel summer T-shirts with butterflies and peace signs, turtlenecks in winter, bell-bottoms all year round, but I didn’t stick to one look every day. “You can’t walk a mile back here hauling groceries. Not along that highway.”

The second that he said it I realized he was right. Just Woody Guthrie’s kibble was too much to haul home. I looked around the yard for a thing to help us carry. The Junk & Stuff was little more than Thor’s small house, a chicken coop, that weathered barn, and a big dirt yard where the flea market set up every other Saturday in summer. It’s why he always let us leave the horses here; there was nothing on his land the two could hurt.

“What about your wheelbarrow?” I pointed to the rusted wheelbarrow propped against the coop. “You think that we could take it into Goodwell?”

“You’ll wheel that a mile on the highway?” Thor said, surprised. “

Then turn around and wheel it back this way?”

“I will,” I said. “I’m strong enough for that. And then I’ll buy a dozen eggs to boot.”

He gave a little laugh. A dozen eggs to boot was Old Finn’s phrase. “Well, listen here,” he said. “If your grandpa’s truck is down, I can drive you to the Need-More. Got to get some groceries there myself. I’m safe enough.” Thor chuckled. “You know I drive the school bus for Goodwell.”

“No thanks,” I said. Even if he let us leave our horses and even if he was Old Finn’s almost-friend, I didn’t want Thor to know we were at Eden all alone. Or that Old Finn was sick now at St. John’s. And St. John’s was the place we needed most to be. “We need to walk in on our own so Elise can earn her badge. Girl Scouts,” I said, like that should be enough. I don’t know how that new lie crossed my mind. Neither of us had ever been a Girl Scout, but last year Nightingale had bought a Junior Girl Scout Handbook for a nickel from a woman at the Junk & Stuff, and this summer the three of us had worked to earn some badges, even Baby, who didn’t count as a girl.

“Girl Scouts?” Thor said. “They got scouts grocery shopping now?”

“Homemaker badge,” I said to sound official. I wasn’t even sure that badge was in the book. Nightingale nudged me with her elbow.

“Well, then.” Thor nodded. “You tell your grandpa that I offered.”

“I will,” I promised. “I’ll tell him that you did.”

5

DOER; DREAMER; DARER

You lied twice,” Nightingale said, alarmed. I looked back toward the Junk & Stuff; Thor was still in that same spot, watching the two of us cross his land out to the highway. “And he didn’t believe the part about the badge. He knew that was a lie.” Nightingale hated lies—even little white ones. Old Finn said she was a stickler for truth.

“Couldn’t be helped,” I said. I steered the wheelbarrow down into the ditch. Old Finn never let us walk along the shoulder. “You know Old Finn doesn’t want folks in his business. And he won’t want anyone to know he left us out at Eden all alone. Not anybody. He won’t want the county to get called.”

Old Finn disliked the county, same way he disliked all government, the war in Vietnam, and Richard Nixon. It’s why the FBI kept a file on Old Finn, followed him around in California, kept track of the history he taught, the books he wrote, the meetings he attended, the help he gave to young men who didn’t want to go to war. He told us it was all those people watching that made him give up on the world and move to Eden, take up his peaceful carving, tend his land, live a life with animals alone. He didn’t want another word written in that file.

What the government gives, he told us in our lessons, the government can take. And every time he said it, we knew that he meant us.

“But we should just keep quiet,” Nightingale argued. “Quiet would be better than a lie.”

“Sometimes quiet doesn’t work, Night,” I said. “Not everyone gets by without a word.”

Old Finn always said the sixteen months between us might as well have been the world. Nightingale and I were so night and day we hardly even looked like sisters. She was small and silent, dark eyed and dark haired just like Daddy, book smart and private like Old Finn. I was tall and talkative, gray eyed with dirt-brown hair, sturdy and strong-minded just like Mama, quick to act, fast to make decisions. Mama used to say I came to earth a doer. Nightingale a dreamer. Baby came to earth a darer—it’s why he tried to fly and why he had twelve stitches in his chin.

Still, different as the Stars were, all of us were part of the same heart—Mama’s heart—and even gone, her love kept us a family. No matter what, we hardly ever fought. I didn’t want to fight with Nightingale now.

The two of us trudged along in silence, the sun beating on our shoulders, the ditch weeds slapping at our skin. Hard as I tried, I couldn’t keep the wheelbarrow from catching in the ruts. Hot blisters rose up on my palms.

“Thor won’t ever know,” I finally said to break the silence. I didn’t want Old Finn to see us in a fight.

“It’s still a lie,” Nightingale insisted.

“It doesn’t matter now,” I said with a sigh. The Texaco was up ahead, and after that the Cat’s Pajamas, an antiques store where tourists liked to shop. Goodwell Pie Place. Butler’s Bait and Tackle with the giant walleye hanging out in front. “We’re almost to Old Finn. He’ll be the one to tell us what to do.”

• • •

St. John’s smelled just like the dentist’s—floor wax and disinfectant and old lady perfume.

“Michael Finnegan,” I asked at the front desk. The clerk didn’t look much older than thirteen—fourteen, maybe fifteen—but she had that perky-bright-blond-ponytailed look from teen-girl magazines. Plus frosty lips and painted nails and a starchy, pink-striped dress. I wished I had my own job at St. John’s so I could be here with Old Finn, earn money for our family, and wear a fancy name pin just like Suzy. Pink and perky Suzy. Only mine would say Kathleen.

She flipped through a roll of cards, then wrote a number on a little slip of paper. “Just so you know,” she said, “I’m not sure he’s having visitors today. Stop by at the nurses’ station first.”

“No visitors?” But we had to see Old Finn. Self-reliant as we were, we still needed Old Finn to say what ought to happen next, how long we’d be at Eden on our own.

“I don’t know.” Suzy shrugged. “Sometimes, they’re just too sick.”

“Too sick?” Nightingale asked.

“He’s not,” I said. I didn’t want Nightingale scared.

Suzy looked beyond us toward the glassy entrance where we’d left the rusted wheelbarrow parked right out in front. “Is there a reason for that thing?” She wrinkled up her perfect, perky nose. Mine was wide and flat and speckled brown from too much sun. “Are you gardening in Goodwell?”

“Buying groceries for my family,” I said proudly. Buying groceries was a job just as much as sitting at a lobby desk flipping through some names. I only wished I had a uniform to wear.

“Okay,” she scoffed. “But the wheelbarrow’s weird.”

6

OLD FINN

Old Finn’s nurse wouldn’t let us in his room. Instead she walked us down the hallway, opened up the door a little crack, and let us have a glimpse of Old Finn dead asleep, his mouth open in an O, his whiskered face dropped over to the side. For the first time in my life Old Finn looked old, broken-down in a way he’d never been. Old Finn chainsawed trees, hoisted bales of hay, put a new roof on the work shop. He still galloped Baby three times through the meadow before we went to sleep. Old Finn was strong enough to do the same with Nightingale and me, but we were just too big for games of horse.

“What are all those things?” I whispered. I could see Old Finn must have needed rest.

“What things?” she asked.

I pointed to the tubes and wires snaking from Old Finn, the machines beside his bed. Old Finn wouldn’t want to be connected to machines.

“Just medicine.” She glanced at Old Finn’s chart. “Are you girls related to Mr. Finnegan?” She looked at us suspiciously, narrowed her eyes at Nightingale dressed in Mama’s baggy shirt.

Bernice, her name tag said, but she had the same bright-white blond hair as perky Suzy, the same frosty pink smeared over her lips.

“He’s our grandpa,” Nightingale answered like she’d already forgotten to keep our business to ourselves. She stared in at Old Finn, her hand pressed against her chest as if she had it on his heart.

“But why is he so sick with just a fever?” I didn’t understand how Old Finn went from well, to sick in bed with just a fever, to wired up in some strange hospital in just a few days’ time. It made me think of Mama leaving us one morning, and by afternoon the sheriff was standing in the driveway saying she was dead. I didn’t want to lose Old Finn like that.

; “Is your mother with you girls by any chance?” Bernice asked me. “Or will she be in today? We’d like to speak with family.”

“She might,” I lied. Nightingale stepped hard on my foot. I hoped up there in heaven Mama would forgive me.

“And is your mother Addie Lee?” Bernice glanced at a note in Old Finn’s chart. “Addie Lee?” she said again. “She’s listed as the next of kin.”

“Mmm-hmmm,” I said. I couldn’t take that lie much further than a hum. Miss Addie was too old to be our mother; if we brought her to St. John’s, the nurse would see that for herself.

“We’ve phoned your home but we haven’t got an answer,” Bernice said. Not our house, we didn’t even own a phone; it must have been Miss Addie’s that she meant. And Miss Addie was at our cabin now.

“But when will he be well?” Nightingale’s big black eyes were wet with worry.

The nurse hung Old Finn’s chart back on a hook, opened up her desk drawer, and handed us two quarters. “Here,” she said. “Why don’t you run along? The hospital’s no place to waste a day. You girls go buy yourselves an ice cream at the Butternut. Your grandpa needs to rest.”

“We’ll watch him rest,” I said. Old Finn would never leave us sick all by ourselves. Last winter, when I had scarlet fever, he hardly left my side.

“Not today,” she said. “A hospital is no place for you children.”

“Can we come again tomorrow?” I said. “Do you think he’ll be awake?”

“I’m afraid that I can’t say,” Bernice said kindly. “But tell your mother the staff would like to see her. To put a plan in place. We’d like to work with family if we could.”

“We’re family,” I said. She could tell me whatever she’d tell Mama.

“I know.” She smiled. “But we’d prefer your mother would come in.”

• • •

“He’s really sick,” Nightingale blurted when we stepped into the lobby. “Really, really sick.”

Keeping Safe the Stars (9781101591215)

Keeping Safe the Stars (9781101591215)