- Home

- O'Connor, Sheila

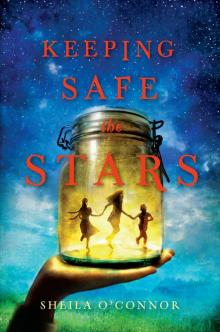

Keeping Safe the Stars (9781101591215) Page 5

Keeping Safe the Stars (9781101591215) Read online

Page 5

“Thor sent home some bacon.” I held up the paper package. “So I’ll fry it for our lunch. Bacon with French toast. Save the SpaghettiOs for supper.” I wasn’t in a hurry to tell the truth about Old Finn. It seemed possible to stay alone with Old Finn just in Goodwell, but harder now that he was in Duluth. So far away and sickly he couldn’t offer any help. Plus we’d need a lot more money now. Money for tickets to Duluth. Electricity and groceries in case we’d be left alone for long.

“But what about Old Finn?” Nightingale repeated. When Nightingale went hunting for an answer she was slow to stop. “Did you get to see him, Pride?”

“Not today,” I said.

“So that nurse knew you weren’t Mama,” Nightingale said like she wanted to be right.

“That wasn’t it,” I said. I didn’t want to think about the costume or the way that Suzy laughed. “I couldn’t see him because Old Finn wasn’t there. They’ve moved him to Duluth.”

“Duluth?” Nightingale gasped. “You mean Old Finn is gone?”

“Not so far,” I said, even though it was. “We can get there on the Greyhound.”

“You mean he isn’t coming home today?” Baby said.

“Not today,” I said. “But soon. He’s going to get well faster in Duluth.”

“Did someone say that, Pride?” Nightingale asked, suspicious. “Or did you just make that up?”

“It’s what the nurse told me,” I said. I didn’t like Nightingale on the lookout for a lie. “But for now, we ought to think about the money. We’re going to need to earn some if we’re getting to Duluth.”

“Money!” Baby clapped. “So then I’ll get my pennies back?”

“You will.” I smiled.

“But how will we get money?” Nightingale asked.

I’d wondered that same question the long ride home from Thor’s. One thing we’d never done is have a job for pay. “I think we have to sell something,” I said. “The way other folks stick signs along the highway for maple syrup or fresh raspberries. Even eggs like Thor.”

“We don’t have chickens, Pride,” Nightingale said like I was stupid. I knew we didn’t have chickens.

“I know,” I huffed. “Those were just examples.” I looked over to the pasture. Scout stood at the fence waiting patiently for Atticus. She’d stay put until he was back there at her side. The two of them couldn’t bear to be apart. “Maybe pony rides?” I said. “Like that carnival those kids put on in Goodwell? That one in some backyard? They had pony rides and games.”

“That was for a charity,” Nightingale said. “Muscular dystrophy. They did it from a kit. And we can’t be a charity.”

“Well, still,” I said.

“Pony rides and popcorn!” Baby jumped up from the dirt. “That’ll be our business. And we’ll sell souvenirs the way they do at Deerland.”

“We don’t have souvenirs,” Nightingale said. She looked over at the pasture. “But maybe we could sell some rides on Scout.”

“We’ll make the souvenirs,” I said. “Like those.” I pointed to Nightingale’s crocheting. She already had a stash of pot holders and bookmarks, lanyard necklaces. I’d made a couple God’s eyes out of yarn and sticks. Baby painted rocks.

“But who would come?” Nightingale said. “That carnival was in the backyard of a house right in downtown Goodwell. And Deerland and the Junk and Stuff are just off the highway. No one ever comes out to our place.”

I shrugged. I didn’t have every answer yet. “We’ll have to get the tourists. Put out signs with arrows so they can find their way to Eden.”

“The tourists Old Finn hates?” Nightingale raised her eyebrows.

“That’s who goes to Deerland. And that’s who buys the maple syrup from the farms.” Every summer, tourists crowded Goodwell, people from the city who vacationed at the lake cabins in northern Minnesota, noisy families who flocked to the resorts. Some of them bought Old Finn’s wooden birds from the Northwood Nook in town. But Old Finn never let them visit Eden.

“He wouldn’t want those folks coming to our cabin,” Nightingale said.

“I know.” There wasn’t any sense to argue otherwise; Old Finn’s opinions were too strong. “But at least it’s self-reliance. And Old Finn would be happy about that.”

14

KEEPSAKES

After lunch we painted up four signs, made stakes out of the broken picket-fence slats we dug out of the barn. Then I stacked them in Baby’s wagon and walked the three long miles back toward town. Hot as it was, I was happier to walk there in the heat than have to ride Atticus to Thor’s place once again. Thor would mean a batch of brand-new questions, another heap of lies I’d have to tell.

PONY RIDES AND POPCORN!!! I stood back and admired Nightingale’s big, bright painted letters. Nightingale’s artwork would get folks out to our place; she’d made our business look happier than Deerland.

When I finally got back to the house, Nightingale had washed a load of laundry and designed the perfect popcorn cone out of paper and some tape. “We’ll use these for serving,” she said. Nightingale always thought ahead. Out back, Baby was leaping from the swing, practicing his flying, even with the stitches in his chin.

“Mama’s darer,” I joked.

Nightingale shook her head. “I can’t keep him off it, Pride.”

“Baby,” I called out the back window. “You weren’t made to fly. And you can’t break another bone with Old Finn in Duluth. I’m not taking you to Goodwell for more stitches.”

“His stitches!” Nightingale said. “Isn’t he supposed to get them out this week?”

I glanced at Old Finn’s calendar. “Looks like it’s tomorrow,” I said. “Three thirty, Dr. Madden. That’s all Old Finn has written for the week.”

“Maybe it can wait,” Nightingale said. “Until Old Finn gets home?”

“Maybe so.” I didn’t know how long stitches stayed, but when I got a job at St. John’s Hospital like Suzy, I could learn about those things. “I’ll go down to Miss Addie’s, call the office, ask if we can wait.”

“You’d call the office, Pride?” Nightingale frowned. “Wouldn’t they wonder why a kid would make that call?”

“Did you see that girl named Suzy? Working at St. John’s? The one dressed like a candy cane?”

“You mean the candy striper who said the wheelbarrow was weird?” Nightingale scowled; she didn’t like her either, and she didn’t even know what Suzy had said today. How she’d called me a hoot.

“Candy striper?” I asked.

“That’s what they call the girls who volunteer. It’s why they’re dressed like peppermints.”

“How old did you think that candy striper was?”

Nightingale shrugged. “I don’t know, fifteen?”

“Right,” I said. “And I’m almost fourteen. So I can call the doctor. Take Baby in tomorrow by myself.”

“You’re only just thirteen.” Nightingale flipped one black braid over her shoulder.

“That’s on the way to fourteen,” I said. “Which means I’m almost fifteen. In another year, I’ll be working at St. John’s. I can take Baby to the doctor.”

Nightingale shook her head, rolled another popcorn cone, and taped the long end closed. “I don’t know, Pride. Sometimes you’re just too sure.”

• • •

I grabbed the dry clothes from the line, carried Old Finn’s basket to his room. There was still a stack of clean clothes left out on his dresser, same place they’d been the days that he was sick. Old Finn’s headache must have hurt him horribly; he never let his clean clothes gather dust. He was always army tidy, the one good thing he said he picked up in the service. And now we hadn’t even made his bed. His old brown quilt had fallen to the floor; Woody Guthrie’s dirty paw prints were stamped across the sheets.

I smoothed the quilt back on the bed, folded Old Finn’s clothes, sorted out his socks, shoved his checkered boxers into a drawer. It felt wrong to be in charge of Old Finn’s clothes; Old Finn liked to handle his own wash. I opened up his sock drawer, stuck a handful in, but then I stopped. I’d never had a glimpse of Old Finn’s sock drawer. It was like a tiny secret chest of private keepsakes: a pocket watch, faded snapshots of Mama as a girl, another one of Mama on a cable car with me. There was a necklace and some medals. Strange coins from other countries. A woman’s ring. And tucked tight against the side, a stack of tissue-paper letters bound by a thin red rubber band. Maybe letters Mama wrote when she was young?

I pulled them from the drawer and held them in my hand. A sweet perfume drifted from the paper. The one on top came all the way from France. Had Mama been to France and I didn’t know it? I felt like I’d discovered some deep secret, some part of Old Finn’s past I wasn’t meant to see. I hid the letters in the waistband of my jeans, pulled my T-shirt down and loose so Nightingale wouldn’t suspect. I knew she’d say to leave them in the drawer, but I just couldn’t. Snooping was a weakness I couldn’t stop. I liked to imagine private things people hid down in their hearts. I’d snuck so many peeks into Nightingale’s diary looking for the secret things she’d never tell me, but most days were just the ordinary things that happened at our house.

“Where you going?” Nightingale asked as I hurried through the kitchen.

“I’m going to say howdy to Miss Addie,” I lied. “Make sure that she’s okay. Maybe give a call to Baby’s doctor.”

“But what about our dinner?” Nightingale said. “Shouldn’t you get it started?” The day had stretched so long I’d lost track of time. Two trips to town, a cake baked, Old Finn in Duluth, a brand-new business started—and I still had to get the family fed. When Old Finn was home, we always ate at five.

“We can run a little late,” I said. “It won’t take me long tonight.” SpaghettiOs were quick to cook; it’s why Old Finn refused to buy them. He didn’t like suppers that came out of a can.

“Why you going to Miss Addie’s?” Nightingale gave me her slow, suspicious stare.

“Just checking in,” I said. “But I’ll get the supper fixed.”

15

DEAR MICK

I didn’t go to Miss Addie’s trailer; instead I ran past Baby on the swing, headed down the wood path, then took my shortcut to the clearing where I sometimes went to think. A little secret dream spot protected by tall pines with a patch of sunlight warming through the trees. It was the perfect private place to steal a look at Old Finn’s letters. I pulled the stack of letters from my jeans, dropped down on the stump. One quick tug, and the worn rubber band just snapped in half. I slipped it into my pocket; I’d have to find a perfect match before Old Finn got home.

I opened up the thin blue sheet of paper; it was an envelope and letter all in one.

Dear Mick, it said. Mick? But Old Finn’s name was Michael. And Mama only ever said Old Finn. Not even “your grandpa” or “my dad.”

September 2, 1972

Dear Mick,

France is absolutely everything I had dreamed and more.

I’m finally here in Avignon after a crazy week in Paris. Seven days of great museums, artists on the streets, that fabulous thick coffee with a froth of steamy milk. Imagining Monet, Picasso or Matisse once painting there in Paris. Sometimes I think I can’t live back in Duluth, but of course come May I will. I wish so much we’d had the chance to see Europe together, but my students have been wonderful, full of curiosity, devouring the work of all the masters. We only managed two days in the Louvre; I could have stayed forever. I could hardly bear to see all that beauty in one place. Someday we’re going to come here, darling, and you’ll be able to see it all yourself. Not the broken Europe you knew back in the war. But how it blooms in peace. Flowers on the boulevards. Flowers in the window boxes. Something lovely growing everywhere.

Today we’re heading to the country for a watercolor class. Maybe I’ll paint you a small picture, so you can see the grass really does glow gold. I want to get this to the post before we catch the train.

I think of you all alone in Eden, but of course I know you like to be alone. Still there’s so much of the world that we could see. Good things that would help you have some hope. Humanity is better than you think.

How’s that sound, Gloomy Gus?

Your love is here with me. And mine with you at Eden.

Justine

Justine? A woman who called Old Finn her darling? A woman who took Old Finn’s love all the way to France?

I looked back at the page. September 2, 1972. Was this Justine living in Duluth? She said she’d be back there come that May; that May would have come and gone last year. But if she was in Duluth why didn’t we know her now? Why didn’t she ever visit here at Eden?

“Pride!” Baby screamed, excited. I tried to stuff the letters back into my jeans, but without the rubber band the stack wouldn’t stay together.

“Pride!” Baby called again. “Our first customer is here!”

“Okay,” I said. I ran back up the path, snuck into Old Finn’s dusty shop. His toolbox was open on the table, his chisels left beside a delicate small cardinal. White curls of wood collected on the floor. If Old Finn were here I’d be working right beside him, building another little birdhouse we’d string up in the tree. My crooked birdhouses hung all over Eden. I didn’t have his patience for the carving—the best I’d ever done was a lopsided wooden heart I’d carved Old Finn for Christmas—but still Old Finn said I had a knack with nails and a hammer. Sureness with a saw. This summer I was starting on a stool.

“Pride!” Baby called again.

I set the letters in his toolbox, latched it closed so they’d stay my private secret. When our first customer was finished, I’d come back for Justine.

16

PONY RIDES AND POPCORN

Our first customer was a worn, ragged mother with three rambunctious boys—all of them Baby’s age or younger, all of them whining loud at once and darting through her legs. I was happy Old Finn wasn’t home to hear it; he couldn’t abide a whine.

“And they call this a vacation?” The woman snarled at me. “Maybe for my husband. All he does is fish.” She slapped the youngest off her leg. “Pajama party?” she said to Nightingale, but Nightingale ignored her. She’d been wearing gowns so long the jokes had grown old.

“I fish,” Baby said. He stuck his pudgy hands into the front pockets of his Wranglers, rocked back on his cowboy boots the way that Old Finn would. Even with a face covered thick in freckles, missing teeth, stubby little legs, Baby liked to think he was a man.

“Well, good for you,” the woman snapped. She rummaged through her purse and pulled out a cigarette case. Then she stuck one in her mouth, clicked a silver lighter, exhaled a cloud of smoke straight into my face. “I guess you have a daddy who cares about his kids.”

“My daddy’s dead,” Baby said. Daddy being dead was a fact since before Baby had been born. Saying it didn’t seem to make him sad. “Old Finn takes me fishing.”

Nightingale sent a worried look my way; Old Finn wouldn’t want us telling our private history to strangers, especially not a tourist smoking in our yard. The less folks know, the better was the way he lived his life. He always said you couldn’t be certain who was asking or what a person might do with your private information once they had it.

I put a hard hand on Baby’s shoulder, squeezed it tight so he knew now to be quiet.

“Oh my,” the woman said. Flecks of dried red lipstick clung to her top teeth. “Well, I’m sorry to hear that.” Suddenly, she stopped and gave us a long stare, studied us the way Bernice had done our first day at St. John’s. Maybe it was Daddy’s being dead or Baby’s strip of stitches or Nightingale’s going barefoot in that nightgown with her black eyes and

small face, but I could tell she thought that we were odd. If strangers were coming to the cabin, Nightingale might have to wear clothes like other kids.

The woman blew another stream of smoke. “You hear that, boys?” she said. “These poor kids don’t even have a daddy. Tell them that you’re sorry.” She slapped another off her leg, yanked the oldest by the arm. “Do what I say, Tommy. Or you’re going in the car.”

“Let go!” Tommy shouted. I couldn’t believe a boy as old as Baby hung from his mother’s dress. Or kicked her in the ankle. Or whined like he was two. “I’m not saying that I’m sorry.”

“It’s okay,” I said. I didn’t need a bratty boy to say that he was sorry about Daddy.

“Did you come here for a ride?” Nightingale asked sternly. I could tell she wanted this woman off our land.

“I’m ready to do anything. You try four days in a cabin with these kids. The beach is filled with weeds. No wonder they’re at each other’s throats. And there’s not a thing to do in Goodwell. Next vacation, I’m going to New York. Alone!”

I grabbed an apple off the tree, coaxed Scout in from the far end of the pasture, and saddled her for business. She wouldn’t like these wild boys any better than we did, but she was calm enough to lead around the yard.

“How much?” the woman said.

“Quarter each,” Nightingale said. “And we got a cone of popcorn for a dime.” We hadn’t popped it yet, but popcorn didn’t take long.

“Quarter each,” the woman said with a laugh. “I guess I can afford that. I can tell you’re not in this to get rich.”

• • •

The whole time the boys were getting rides on Scout, the woman perched on Baby’s swing and smoked, ashed her cigarettes right in Old Finn’s grass, ground them out, and left her lipsticked butts right where Baby played. And every time I tried to tell each dirty boy his turn was over, he’d pitch such a terrible fuss, she’d order me to let him ride a little longer. Longer still. I walked circles through the yard so she could smoke.

Keeping Safe the Stars (9781101591215)

Keeping Safe the Stars (9781101591215)