- Home

- O'Connor, Sheila

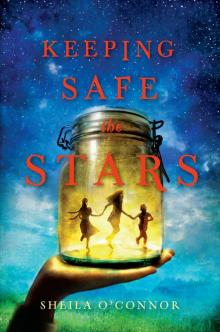

Keeping Safe the Stars (9781101591215) Page 11

Keeping Safe the Stars (9781101591215) Read online

Page 11

“Best deal in town,” Nash said. “You kids ought to work for Wall Street.” He stood up from the step, lifted up his camera, and shot our souvenirs. A long, clicking string of pictures. “God’s eyes,” he said. “You got to love these things. Ojos de Dios. I remember making them at church camp.”

I couldn’t imagine Nash winding yarn through sticks. “I learned them at Serenity,” I said. I’d never been to church camp. “Skye taught me in the craft hut.”

“Serenity?”

“A place we used to live,” I said. “Down in New Mexico.”

“New Mexico?” Nash opened up his eyes wide, but he didn’t write that down. “I did a piece once on New Mexico. Santa Fe.”

“You’ve been to Santa Fe?” I said, surprised. We hadn’t met a soul in Goodwell who’d been to Santa Fe.

“Sure,” Nash said. “Great place.”

“Did you see the artist market?” I said. “Mama took us there. Or the old woman in the square who sold those cookies?”

“Powdered sugar?” Nash smiled. “I loved those things!”

“Yes, those!” I said. “With jelly in the center.”

“I guess that’s where you kids got your magic spirit,” Nash said. “There’s enchantment in New Mexico. I had a sense you came from someplace else. But I was thinking Fairyland.” He laughed.

“Serenity,” I said. “It was a commune in the mountains. With ponies and a stream.” Mama always said hardly anyone grew up in a commune, and someday we’d see it made us special. But Serenity was something we hardly talked about at Eden, because everything about it just upset Old Finn. “And we got to go to free school.” Free school was my favorite part. Not Daniel Walker. Or how Daddy’s cancer didn’t get cured there the way Mama hoped it would. Or Mama dying in that van. But there were good things at Serenity I’d loved.

“Free school? Now there’s an oxymoron. What in the world is free school?” He took a photo of the cookie jar.

“It’s where you get to study what you want. You don’t have to read,” I said, but maybe that’s why I didn’t know what oxy-something meant. “Or do number work. So I hardly ever worked at either one. I liked taking care of toddlers in the kids’ yard or kneading bread or baking cakes. Or tending to the ponies. We had four ponies there.” Telling this to Nash made me proud of where I’d come from, because no one else’s story was anything like ours. Now maybe he could write about Serenity; forget the charity and lies. Serenity was true.

“Terrific,” he said. “I want to sign Sage up. And what was it? Serenity?” He patted at the pocket of his shirt, where he kept that tiny notebook.

“Yep,” I said.

“Great name. Serenity. So why’d you leave? How’d you end up living way up north?”

“Oh.” I stalled. I couldn’t say Mama died because now she was a painter. “The peace,” I said. “Mama liked the peace where Old Finn lived.” Peace was true; it could be in the magazine.

“I get that,” Nash said. “It certainly is peaceful. So your mom? Any chance that I could catch her before she heads off to paint?”

“Too late,” I said. I could feel the heat climbing up my face; suddenly I’d gone from truth to lies. “She’s already left.”

“Then Old Finn?” he asked. “That’s your grandpa, right?”

“Yep,” I said. “But he’s sort of like a hermit.” A hermit wouldn’t come out to talk to Nash. “Do you know what that is?”

“I do.” Nash smiled. “He keeps off to himself.”

“That’s it,” I said. “Exactly.”

“I understand,” Nash said. “But I wonder if we might just have a word.”

31

NOT ANY NUMBER HERE

I told Nash Old Finn was in Duluth. I didn’t say that he got sent there sick; I said he’d gone to sell his carvings to a store. It was a story Nash seemed to take as truth.

“Ah, right,” Nash said. “He carves. I saw his work in Goodwell. Found it at the Northwood Nook, exactly like you said.”

“You did?” I couldn’t believe he looked for Old Finn’s work.

“I’d have liked one of his loons, but I didn’t have the cash. Got to watch my money on the road. They don’t exactly pay you millions to do a freelance gig, especially this travel magazine.” I felt bad for taking Nash’s money; he didn’t seem to have much more than us. “But at least the owner of the Junk and Stuff let us crash out at his place, park the van out in his yard so we could sleep.”

“Thor?” I said. Nash and Sage met Thor?

“Yep,” he said. “Thor Jensen, that’s the guy. Super-kind. But I didn’t want to waste the welcome. I figured we’d get on our way before he felt obliged to offer breakfast.”

“He lets us leave our horses at his place. It’s the closest we can ride them into town.”

“That’s what he said.” Nash looked out at our fields. “Said he’d seen you earlier that day. He seemed surprised about your business. Said your grandpa wasn’t one to take to tourists.”

A lump rose in my throat. Did Nash tell Thor about the charity? Did Thor tell Nash our parents were both dead? I didn’t know how much Thor knew about our family, but I was sure he knew that we were orphans, why else would we be living with Old Finn. Same with Nosy Nellie at the Northwood Nook in town. If Nash asked her, she’d have said the same.

“Did you tell Thor about the travel magazine? The story you might write?” I tried to keep the tremble from my voice. I didn’t want either of them to see me as a liar, but once they started talking they could figure that part out.

“No,” he said. “No one trusts a journalist. Especially these days. Half the country blames us for destroying Richard Nixon. The other half adores us. I never know which half I’ve wandered into. I just said I’d brought Sage out here for a ride.” He pulled his little notebook from his pocket, flipped it open to a page. “But that phone number you gave me? That’s not any number here.”

“It’s not?” I said. “I guess I was confused. We haven’t lived here all that long.”

“No?” Nash squinted.

“And I guess I don’t call home.”

Nash rubbed his hand along his whiskered chin like he was thinking. “You know,” he said. “I’m just writing freelance for a travel magazine. It’s not like I’m cracking Watergate.” I rearranged the items on the shelf. I wished something huge would happen, something big that would stop the conversation. Baby dropping from the swing. Another set of stitches. “And still . . .” He stopped like he was looking for the words. “Sometimes you stumble on a story. Something bigger than the one you thought you’d started.”

“You want to pick your souvenirs?” I interrupted. I didn’t like Nash’s voice. “We’ve got to start our school.”

“Right now? School in the summer?”

“We learn at the table,” I said. “Year-round. And we have to get our lessons done.” We hadn’t had a minute for our lessons since Old Finn went in sick, but I’d be happy to start now if it meant that Nash would leave. We could give them up once he was gone. “Baby!” I shouted. “Come in for your reading.”

“Mind if I just wait?” he asked. “For your grandpa or your mom?”

“You should come back later. Someone ought to be here.”

“Like when?”

But before I had an answer, a station wagon pulled into our yard. That mean woman and her dreadful boys were back.

32

CABIN FEVER

This is it.” The woman stepped out of the car, waved her cigarette in my direction. She was dressed in an old housecoat, and today her hair was twisted tight into a halo of bobby pins and big pink plastic rollers.

“Jeanette.” Her husband shook his head. He looked like most of the tourist men we saw in Goodwell—pale legs, black socks with fishing shorts, a sporty s

hirt with a penguin stitched into the pocket, his face and arms burned red from too much sun.

Nash flipped to a blank page. “You know these folks?” he asked me.

“No,” I said. “Not really.”

The bratty boys scrambled from the car. “That’s her,” Tommy shouted. “She’s the girl who yanked me off the horse.”

“When was that?” Nash asked. He was writing down each word.

“I didn’t,” I said. I wanted something big to happen, but this big wasn’t it. “I dropped him when he kicked me in the stomach.”

“And then she had the nerve to ask for money,” the woman said to Nash. She took a long suck on her cigarette. “Show him how you limp.” She reached down and shoved Tommy forward a few steps. At first he made a little hobble, then he walked like anybody else. “His ankle’s sprained.”

“Jeanette,” the husband snapped so she’d shut up. He looked around the yard. “Is this operation licensed and insured?” he asked Nash.

“I’m just a customer,” Nash said. He took the lid off the rooster jar. “A nickel each,” he tried to joke. “And they’re really, really good.” He held the jar out to the man in the black socks.

“So who’s in charge?” The father stared at me.

“I am,” I said. “I’m in charge this morning.”

“Are you versed in liability?” he asked me.

“She’s a kid,” Nash said. “She hasn’t studied law.” I could see he didn’t like these people either. Not even the husband.

“Have you?” he barked at Nash.

“Not a drop,” Nash said. Compared to all the tourists, Nash really looked like a hippie—his curls too long, his bare feet tan and dirty in strappy leather sandals, his clothes gray and wrinkled from living on the road.

“We need to speak to the person who’s responsible. You can’t operate a business without being insured.”

“It’s not a business,” Nash said. “They raise money for a charity. Three sweet kids have set this up. They’re not going to have insurance.”

“Regardless,” the father said. “If my son’s injury is serious, someone here will pay.”

“How much?” I said. We still needed money for our tickets to Duluth. “You can take some souvenirs. For free.” I was glad Nightingale wasn’t here to see this family take her crosses.

“That crap?” the woman scoffed. “Is that supposed to pay our bills?”

“Jeanette,” the husband said again. “Why don’t you and the boys get in the car? Let me handle business.”

“I want popcorn,” one boy whined. “I don’t want those cookies.”

“There isn’t any popcorn,” I said. I wanted everyone to leave. I wanted to go back to being just the Stars. Three kids in the cabin by ourselves. As soon as they were gone I’d take the signs down from the highway. Find another way to make the money for the bus. It’d been nothing but big trouble to let strangers come to Eden. Old Finn was right—everything was easier alone.

“We want to see your mother,” the woman ordered. She grabbed one boy by the arm and shoved him into the car. “The rest of you get in,” she said. “There isn’t any popcorn.”

“She’s dead,” Nightingale said. I glanced over at the cabin. Nightingale was at the door watching this whole scene. Then she stepped out in her nightgown, her long black hair woven in fresh braids. Maybe she hadn’t gone to Miss Addie’s after all. “Our parents are both dead.” Her face was serious and solid; her dark sheep eyes didn’t blink.

“Is that true?” the man asked Nash.

“I would assume—” Nash said, but I couldn’t look in his direction.

“I thought your brother said your dad was dead. Your dad,” the woman said.

“He did,” I said. “But both of them are gone.”

“You know,” Nash said a little softer, “if your son’s not badly hurt, why don’t you let it be?”

“Well, someone still should pay,” the woman urged her husband. She ground her cigarette into the grass. “Dead or not, these kids don’t live out here all alone. Someone’s making money off this business. Selling rides and harming helpless victims like poor Tommy.”

“Let’s goooooooo.” A high-pitched whine came from the back window. “I want to go to Deerland.” Up in the front seat, Tommy leaned hard on the horn, so loud and long, Sage and Baby came running from the woods.

“I want to talk to somebody,” the woman said. “If you can’t produce a parent, we’ll talk to the police. Some adult will answer for your actions.”

“Now, Jeanette,” the husband said. He reached into his pocket and jangled his loose coins. “If these children are real orphans, why not let it rest.”

“It’s the principle!” She climbed into the car and slammed the door. “You just go back to fishing, Henry,” she shouted at her husband. “Go back on your boat! I’ll take care of this.”

“Oh, for heaven’s sake.” He snatched a couple cookies from the jar, put a quarter in my hand. “The wife’s got cabin fever.” He rolled his eyes at Nash. “Next year, I’m coming fishing all alone.”

33

COULD BE THIS AFTERNOON

Are they calling the police, Pride?” Baby wrapped his arms around my waist, pressed his sticky cheek against my shirt. “Why’d that horrible woman come back to our cabin?”

“I don’t know,” I said. I hoped this wasn’t going in our story. This, or Mama’s death. I didn’t want either one in Nash’s magazine. “She was mad her son got hurt.”

“But he kicked you in the stomach,” Baby said. “And they didn’t pay.”

Sage crawled into Nash’s lap, laid her head against his chest, stuck two fingers in her mouth like she was scared. “You kids have fun?” Nash asked. He didn’t say a word about Mama’s being dead; he just kissed Sage on the head the way Daddy did to me. I wished I were still small enough to sit on someone’s lap. “So your mother isn’t painting in the fields?” Nash said finally. He asked the question kind enough, but I could tell he wasn’t happy.

“No,” I mumbled.

“And is she really dead?” He looked at Nightingale.

“She is,” I said. I wanted some little piece of truth to come from me.

“And is your last name really Matisse?”

“No.” I hung my head. “Our last name is . . .” I wanted to say Guthrie, but I just told him Star.

“Star?” he questioned as if he thought our last name was just another lie. “With two rs?”

“One. But will you put that in your story?”

“The part about your mother?” he said gently.

“Mama or our names,” I said. “You can’t call us the Stars.” I couldn’t tell Nash about the county or the file the government once kept on Old Finn’s life, but I also couldn’t let him say we were the Stars. “If you don’t like Matisse, Guthrie would work fine.”

“Like the dog?” He stared at me. “Why don’t we just go back to the facts? Start with those and get them straight?”

I could have told the whole truth at that minute, but I’d already said Old Finn was in Duluth; I’d only left out the part that he was sick. I pressed my fingers into Baby’s neck so he’d stay quiet. Gave Nightingale a glance so she wouldn’t interrupt.

“We live here with Old Finn,” I said. “But we don’t like to tell the world we’re orphans. And we always keep our last name to ourselves.”

“Okay,” Nash said slowly, like he didn’t trust my explanation. “And where’s Old Finn today? And yesterday? Who’s watching you right now?”

“Old Finn’s off in Duluth just like I said. He really is. And we’re watched over by Miss Addie until Old Finn gets back. Which will probably be soon. Her trailer’s on the wood path, so we’re not out here at Eden all alone.”

“Soon?” Nash

asked. “Like when?”

“Could be this afternoon,” I said. It could. I didn’t know when he’d be home.

Nash ran his hand over Sage’s curls. “Any chance that I could have a conversation with Miss Addie? Or is she a hermit, too?”

“She sort of is,” I said.

“I just need to know you have someone on this place. Substantiate this story.”

“Substantiate?” I asked.

“Make sure it’s true before it’s in a magazine.”

“It’s still in the magazine?” Nightingale complained. “We don’t want it printed, not a word.”

“Well, let’s just wait and see,” Nash said. “Let’s start off with Miss Addie. I’d like to ask a couple questions.”

“Okay,” I finally said. We needed Nash to go. “But first I have to ask her because she’s not much used to guests.”

“And I’ll give Sage some Sugar Smacks,” Baby blurted. “We didn’t eat our breakfast yet.”

“We’re all out of Sugar Smacks,” I lied. I didn’t want them staying long enough to eat.

“No,” Baby said. “We still have half the box.”

• • •

I led Nash down the wood path to the trailer while Nightingale stayed behind to keep an eye on Sage and Baby; I knew she didn’t want to listen to more lies. “You wait outside,” I said. “I ought to have a word first with Miss Addie.”

“Right.” Nash pulled his notebook from his pocket. “I’ll just jot some notes down while I wait.”

I wished he wouldn’t keep writing; I didn’t want every bad part of this story in some travel magazine. Especially the part about that woman and her husband. Or Mama’s being dead. Or the lies I told this morning.

“Hey, Miss Addie.” I walked to her TV to turn the volume down. She was dozing in her rocker, a movie magazine spread open in her lap. I gave her a quick shake. “Someone’s here to meet you.”

Keeping Safe the Stars (9781101591215)

Keeping Safe the Stars (9781101591215)